Иллюстрация Екатерина Балеевская/SpektrPress

Иллюстрация Екатерина Балеевская/SpektrPress

You can read this publication in RUS and LAT

Online magazine «Spektr. Press» together with independent sociologist Olga Procevska and the Latvian public opinion research agency SKDS have conducted an unusual survey titled «Risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events».

The survey was conducted in March 2023. It was based on two nationwide surveys in Latvia — face-to-face (1020 respondents) at the place of residence and online (1231 respondents) with a representative sample (i.e., representing a cross-section) of 18 to 75 years of age. Of the total number of respondents, 1191 have Latvian as their mother tongue, and another 1039 are Russian speakers (who speak Russian in the family).

Risk tolerance

The term «risk tolerance» came to sociological research from behavioral economics — a branch of economic research not very popular in Latvia, but rapidly developing in the world, which studies the influence of social, cognitive and emotional factors on the behavior of individuals and organisations.

In psychology, it determines, among other things, the level of risk an individual is ready to take when taking an action or pursuing a particular goal. Risk appetite as a basic personality trait has been shown to influence decision-making not only in economics, but in a wide range of human activities. Why did the authors of the study decide to look at the preferences and opinions of the Latvian population through such an unconventional prism?

«There is a myth in Latvia that Russian-speaking Latvians are more enterprising and willing to take risks,» explains Olga Procevska. — Most probably, due to the fact that some figures of Russian-speaking entrepreneurs who have made a lot of money are visible in the public space». Until now, researchers have had no data on whether Russian-speakers actually do more entrepreneurship and self-employment than Latvians. «We have assumed that yes, because they have nothing to lose but their shackles,» says the sociologist. — Especially poor Russian-speaking non-Latvians, who are not in the centre of the society economically and socially».

The starting point of the study was the question whether their deprived status (deprivation — loss, preclusion; that is, sustaunably low-income and distanced from social medium strata stuck at the level of relatively stable survival — «Spektr. Press») is transformed into a desire to break forth «on top», which eventually leads to a greater entrepreneurial spirit, explains Olga Procevska: «In my circle, there is also a number of people who came from the grassroots. I wanted to see how it looked in the society as a whole.»

The key term for the study was «risk tolerance», which is often defined as the propensity for risky decisions (e.g. in investment, finance). This concept has already been fairly well studied in other countries. It is known what factors determine the formation of this quality and how it itself, in turn, influences decision-making and human behavior.

It is not just about the financial sphere. Olga Procevska explains that people who are more tolerant of risk are on average more likely to become entrepreneurs, invest more in education, are more likely to migrate, including between countries, and are also more likely to use new medicines, including vaccines. But they are also more likely to gamble, do things that are unhealthy and more likely to pay bribes, because corruption is risky behavior.

Risk-tolerant people are more likely to take to the streets to protest, to vote for the new parties. «Risk tolerance is a fundamental characteristic of an individual, -» explains the researcher. — That is why it was interesting for us to study all this in the context of Latvia as a country that has undergone a major historical transformation.

Who drinks champagne?

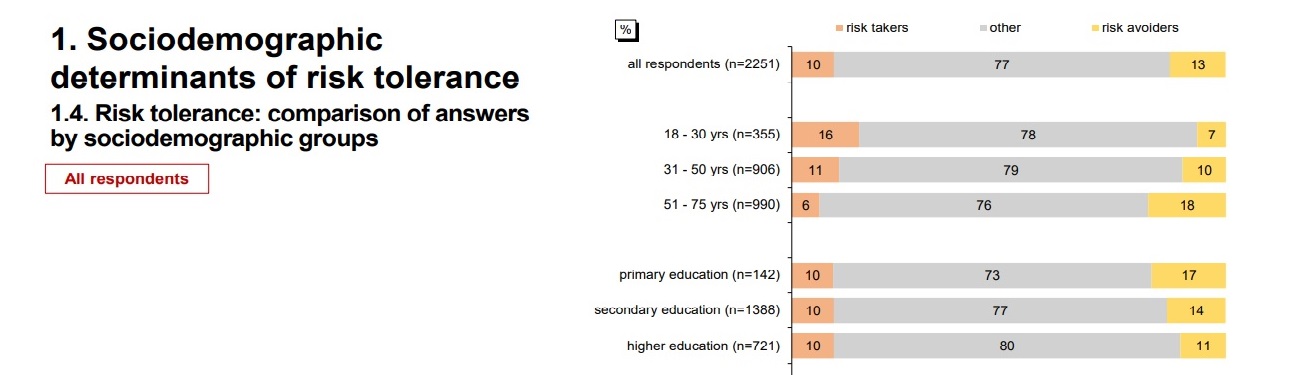

People who are willing to take risks actually turned out to be rather few in Latvia - 10 percent of the total number of respondents. And those who are completely unprepared for it are also a little more — 13 percent. Risk tolerance is highly influenced by family background and a sense of security in childhood and adolescence: among Latvians — 11 percent take risks, and among Russian speakers only 8 percent (the difference, however, is within the margin of error).

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

The hypothesis that Russian-speakers in Latvia are more risk-averse than respondents who speak Latvian at home was not confirmed, which, according to Olga Procevska, is also a valuable finding. «Often societies feel that they are unique,» she explains. — Russian society, for example, suffers greatly from this.»

The study was wonderful in that the researchers really did not know how the cards would fall, the results came as a surprise, says the sociologist. «[It turned out that] people coming from poor families were less likely to take risks than those coming from affluent families. The ethnic dimension here manifested itself only in the fact that Russians in general are poorer, and if one is a poor Russian, one’s risk tolerance profile is predictably the lowest. It is the highest if you are a young affluent Latvian».

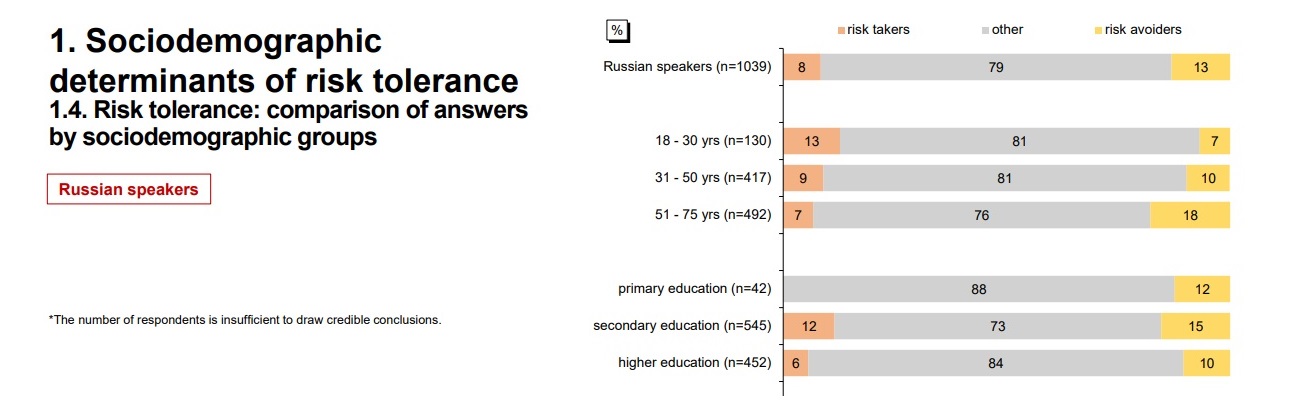

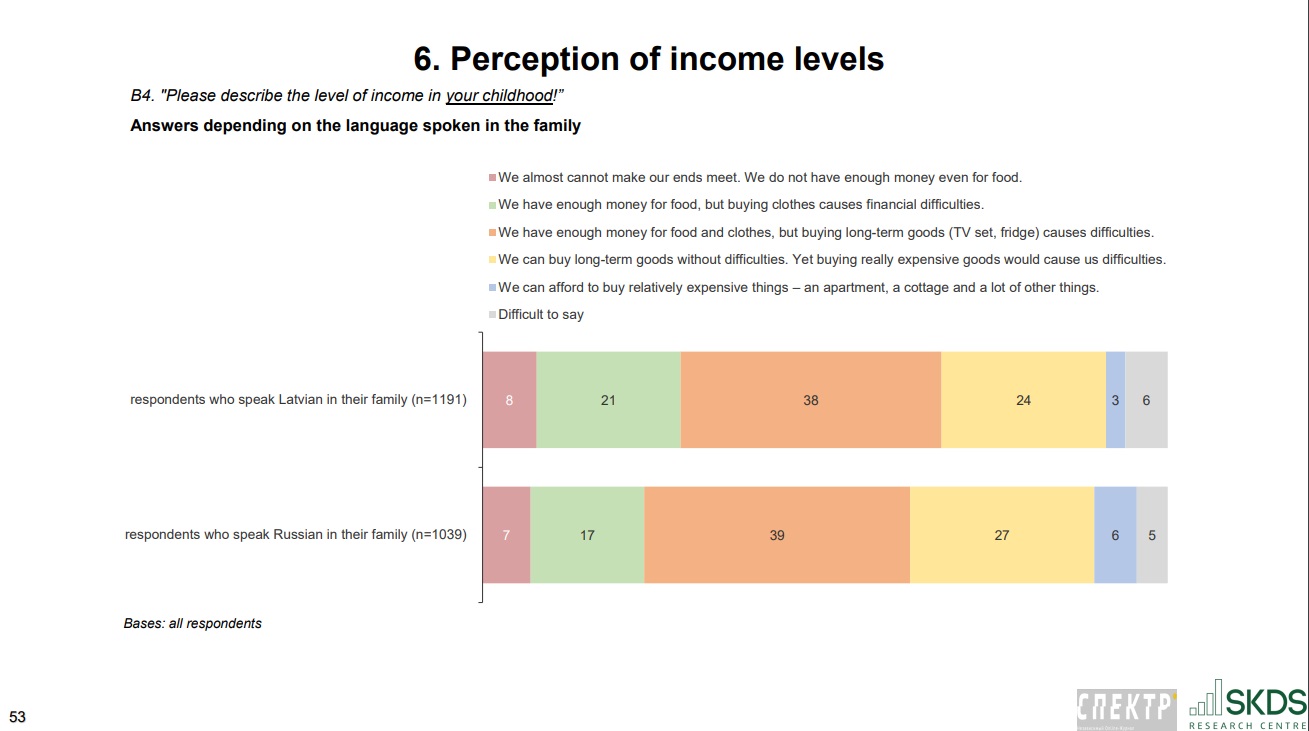

The authors of the survey did not specify the family’s monthly income when they asked about the level of wealth of the respondents. They wanted to know how the level of welfare was perceived. Standard SKDS questions were used. At the bottom of the scale are those who agreed with the statement «we cannot make ends meet, not even enough money for food». Next were those who «had enough money for food, but buying clothes already caused difficulties».

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

«Both categories are objectively poor people», explains Olga Procevska. Those who have «enough money for food and clothes, but it causes difficulties for them to buy durable goods, such as refrigerator or TV set» are ranked higher. This category includes the largest part of the Latvian society. Still higher are those who «can buy durable goods without difficulties, but it is difficult for them to buy expensive goods.» This category already lives in affluence. And the option «we can afford both a flat and a summer cottage, and other expensive purchases» was chosen by very rich people. There are only two percent of them in the survey.

Respondents were also asked to assess the well-being of their family during their childhood, because this factor influences the formation of risk tolerance. It is known that the poorer the family a person comes from, the lower his/her willingness and desire to take risks. In other words, if a person was poor, he/she is likely to stay poor, according to the researcher. As the data show, among the Russian-speaking residents of Latvia there are more people with subjectively low-income than among Latvians — in contrast to the estimates of family life in childhood.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

The survey also asked whether the person has any experience in self-employment. 26 per cent of the respondents with the native Latvian language answered that they are or have been entrepreneurs or self-employed once in their life. Among Russian-speaking respondents there are 23 per cent. The difference is within statistical error; thus, one can say, it does not show up in the linguistic cross-section. In other words, in Latvian reality none of the language groups demonstrates outstanding entrepreneurial activity.

How was the risk appetite investigated? The respondents were asked two questions. The first one was: «Imagine that you participate in a game and you can choose a 50 euro guaranteed prize or participate in a lottery where only one out of 10 tickets wins 1000 euros and the rest are empty». The answer was asked to be marked on a scale of probability. The second question asked the respondent to rate in points the extent to which they are generally inclined to take risks in everyday life. «This is common international practice. A combination of these questions is usually used to assess the objective level of risk tolerance of each respondent,» explains the researcher.

Based on the results of the survey, participants were divided into three groups. «Risk takers» are those who chose the lottery and subjectively rated their risk appetite at 8−10 points out of 10. Risk avoiders were those who chose a guaranteed prize and rated their risk appetite at 1−3 points. The rest fell into the «others» group. «Risk takers» accounted for 10 per cent of all respondents and avoiders for 13 per cent.

Among the «risk-averse» respondents, 13 per cent are or have been in business, while among the avoidant respondents, they constitute 11 per cent. The difference is small. 9% of risk-takers and 13% of risk-averse respondents answered «Never been into business». If we add the language attribute, the difference becomes larger: among Latvians, the risk takers are 15 per cent. «This is already a statistically relevant difference», says Procevska. Among the Russian-speaking risk takers, 12 per cent are entrepreneurs. This is also more than the average, but less than among Latvians (but close to the margin of error).

- Describing risk takers it can be observed that 24% of this group in childhood were poor or near poor, 39% — below middle class, and 29% — middle class and rich. On the other hand, 30% of risk avoiders in childhood were poor or near poor, 35% were below middle class, and 30% — middle class and rich.

- When describing risk takers it can be observed that 17% of this group are poor or near poor, 47% — below middle class, and 36% — middle class and rich. On the other hand, 31% of risk avoiders are poor or near poor, 45% are below middle class, and 24% — middle class and rich.

- It should be noted that 33% of risk takers said they are or have been self-employed or business owners (66% never have been), while 22% of risk avoiders said this (77% never have been self-employed or business owners).

The poor keep silent

A classic poverty trap emerges. «If you come from a poor family, it affects you in different ways,» explains Olga Procevska. — To use Pierre Bourdieu’s terminology, you have less not only economic but also social and cultural capital. In other words, you have fewer connections, less education and fewer opportunities to build your life up the social ladder on the basis of this capital. Among other things, poverty in childhood gives a person less risk tolerance and thus less chance of becoming an entrepreneur — which is, after all, a way to raise oneself the crowd».

What follows from this? «A neo-liberal would say that poverty has always been and always will be, and it is not our problem, because whoever wants it will always make it,» says Procevska. — I do not share that view. Especially in such a small society as Latvia, we cannot afford not to develop the talents of poor people. It would be in the tradition of social democrats to start state interventions. They are well-known. First of all, we can simply give money to poor people. There is an intervention called «allowances». This topic is much less discussed in Latvia than it affects us. According to international studies, 25% of the population of Latvia is at risk of poverty. Now these people can make ends meet, but their car breaks down and they cannot afford to fix it. Or they cannot afford to have their teeth cured. And that is very bad for the society.

The other big intervention, according to the researcher, must be in the field of education. «In post-war Europe, universal education, starting in kindergartens, was a means of reducing inequalities in society, levelling out differences in backgrounds,» she explains. — Because if everybody goes to the same kindergartens and schools, those who come from lower strata are pulled up to the general level. In Latvia, de facto, this does not happen: people who are wealthy send their children to private kindergartens and schools and then study abroad».

Another important factor influencing the situation is migration. Olga Procevska reminds of a study by Mikhail Hazan, professor of the University of Latvia, according to which about 200−300 thousand people left Latvia immediately after the 2008 crisis as a result of the «belt-tightening policy». This is a huge figure for Latvia, and, according to Procevska, this numerical loss can be multiplied by the risk tolerance coefficient — because it is known that the higher it is, the more inclined an individual is to migrate.

«It can be assumed that those who left are actually more entrepreneurial people than the average resident,» says the researcher. — This increases the negative economic effect of this kind of migration. Our research shows that the effects will be noticeable in another generation. Poverty has a certain viscosity. It must be the number one issue on the political agenda of Latvia. However, other issues are being discussed here».

The NATO discord

The study consists of three parts. The first deals with traditional issues in Latvia: attitudes towards the country’s membership in international organisations, the events in Ukraine and voting in the last elections. The second focuses on the stated topic: risk tolerance. Researchers then found out the correlation between this indicator and responses to the current agenda.

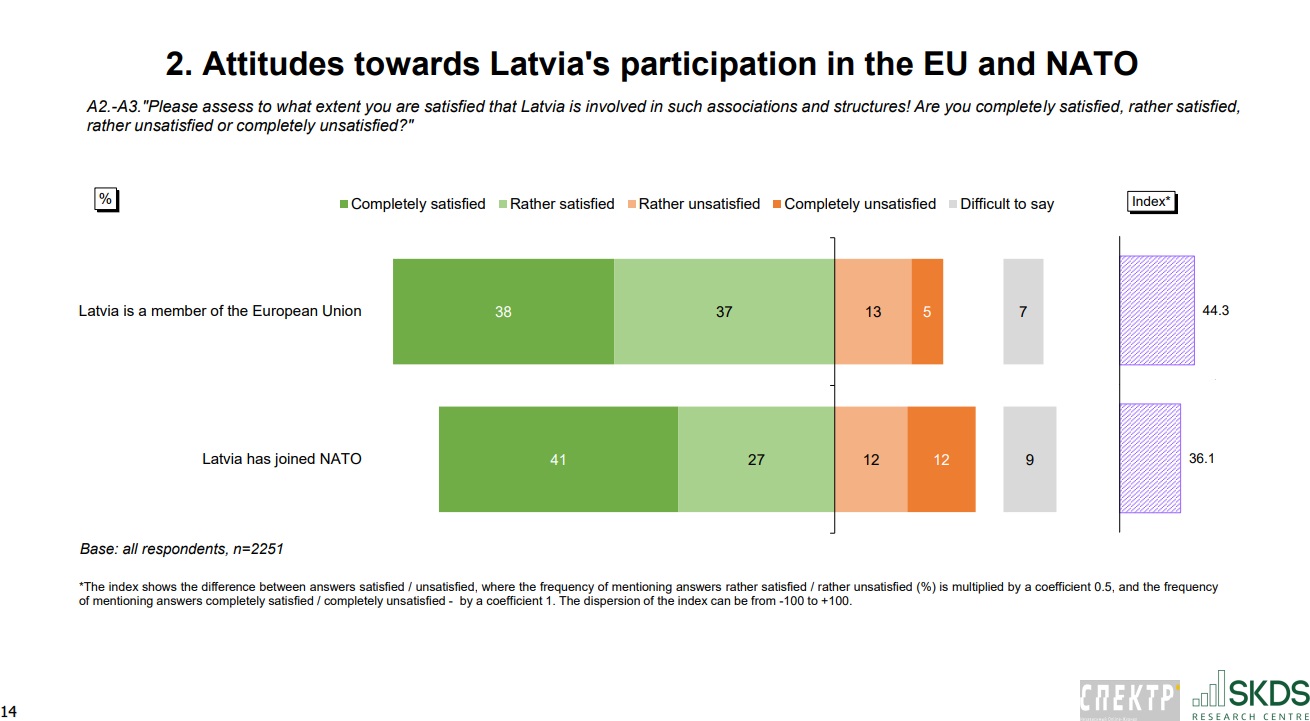

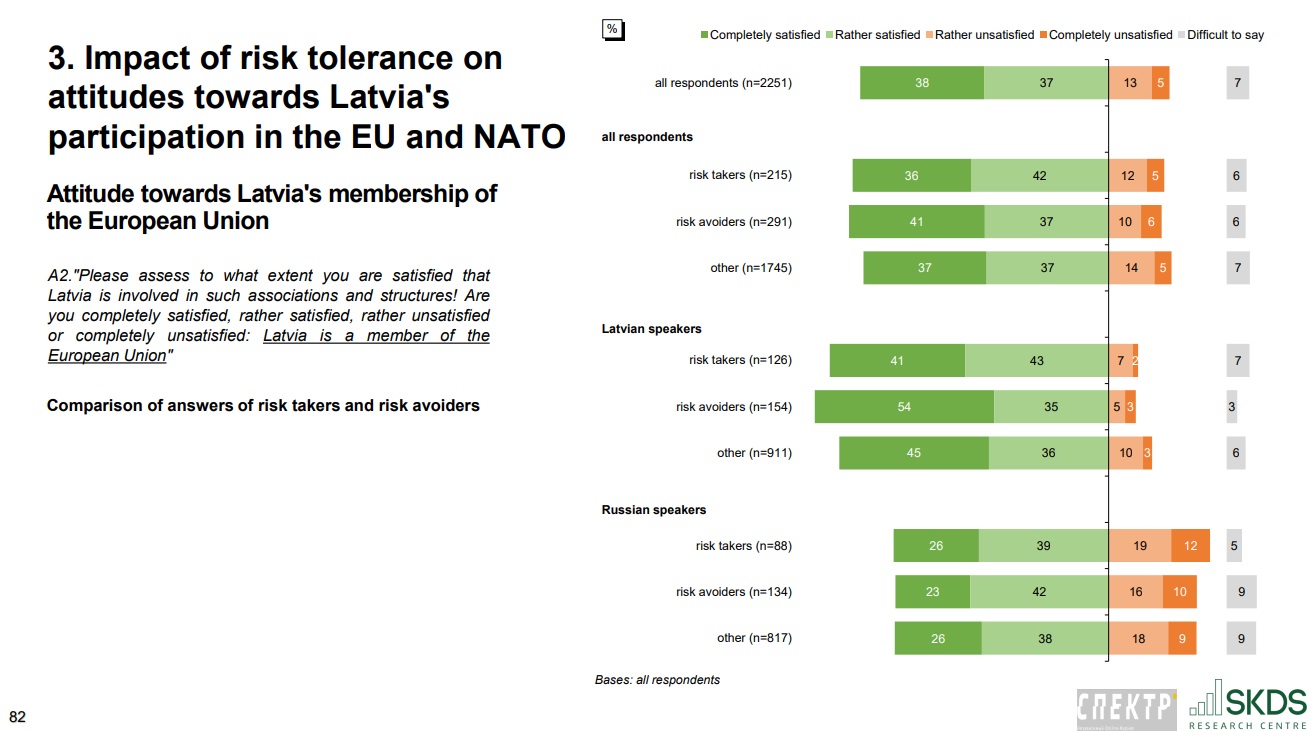

Thus, 75 percent of the respondents are сontent with Latvia’s participation in the EU: 38 per cent — completely, 37 per cent are well-content. Dissatisfied are 18 per cent: partially — 13 per cent, completely — five per cent. As usual, there are more content Latvians than Russians, but among the latter, there are more Euro optimists than Eurosceptics in all the three risk attitude groups. Of significant differences, the following can be mentioned. Among risk-averse Latvians, there are the most unequivocal supporters of the EU membership: 54% (41% among risk-takers and 45% among «others»). The greatest share of Eurosceptics (against and rather against) among the risk-averse Russians attracts attention: 31%, whereas 26% among the risk-averse and 27% among the «others».

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

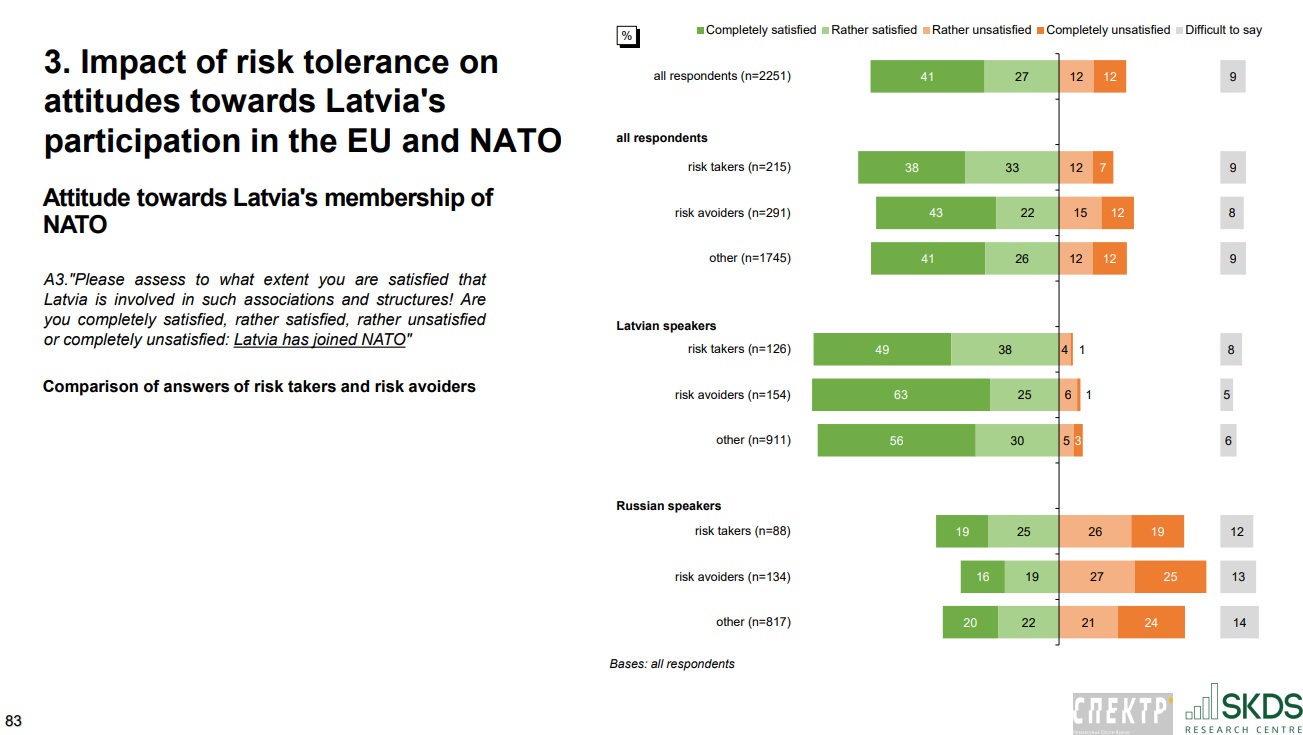

Attitudes towards NATO show a split in society. While only 41 percent of Russian-speakers are satisfied with Latvia’s membership in the bloc, 86 percent of Latvians are. «In general, it is known that support for NATO (and EU) in the Latvian society has increased sharply since last February, including among Russian speakers, but not to the same extent as among Latvians,» reminds Olga Procevska.

She also notes a paradoxical situation: support for NATO is almost absent among risk-averse Russians (16%, compared to 19% and 20% among risk-takers and «others» respectively), while uncompromising supporters of the alliance are at their peak among Latvians in the same group: 63 per cent, compared to 49 per cent among the risk-averse and 56 per cent among the «others». This number is significantly higher than in the general population.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

«However, it is important to understand that sometimes these results correlate not with the risk tolerance per se, but with the factors that determine it: level of affluence and age,» explains the researcher. — And we cannot exactly establish a causal relationship. In principle, speculation in this area is somewhat justified by the fact that NATO is a collective defence organisation, and if you avoid risk, it is logical to support it.»

It is interesting to compare these figures with data from more than two years ago. In 2020, the online magazine Spektr and the Public Opinion Research Center SKDS, with the support of the Embassy of the Netherlands and the Embassy of Sweden in Latvia, conducted a sociological study that showed that the vast majority of Russian-speaking residents of Latvia — 73 percent — are Europeans in their views, and perceive themselves that way. At that time, Latvia’s membership in the EU satisfied 70% of the Russian-speaking residents of the country surveyed (today this figure has decreased and is 65%), while only 32% of respondents were satisfied with joining NATO (by 2023, this figure increased by 9 percentage points and currently stands at 41%).

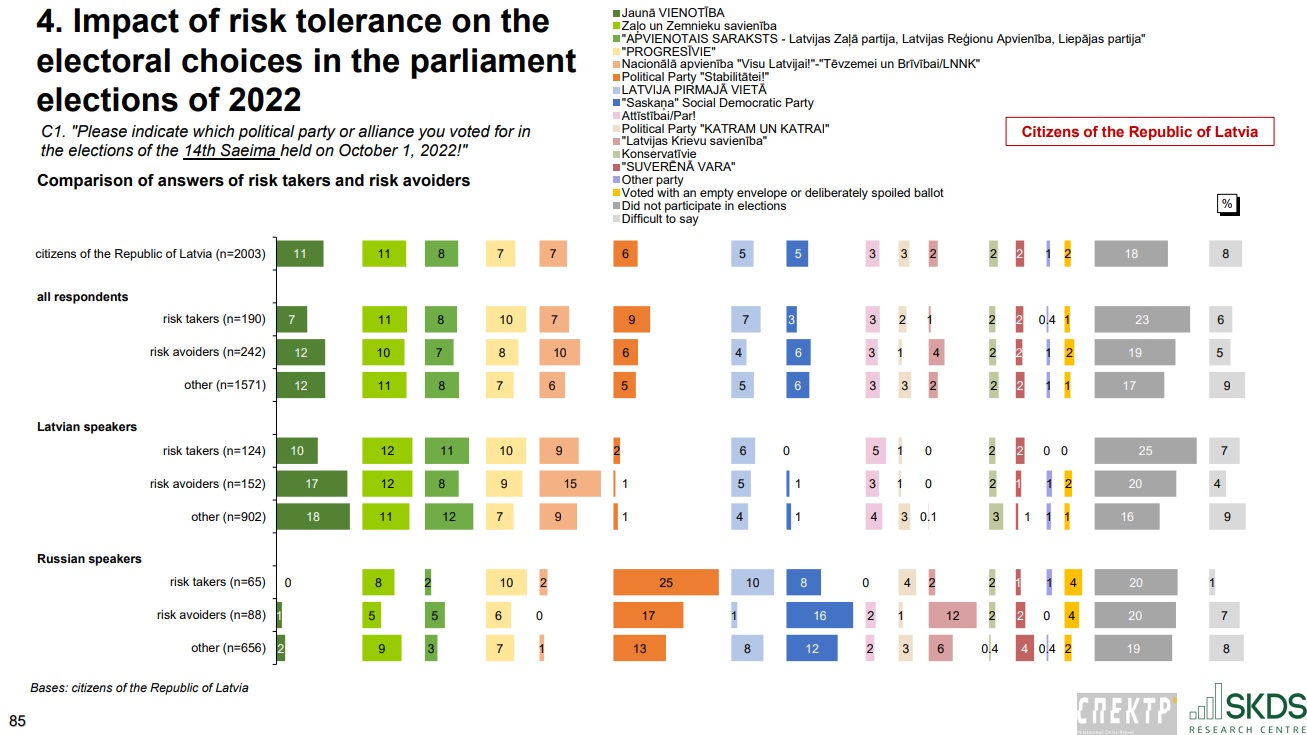

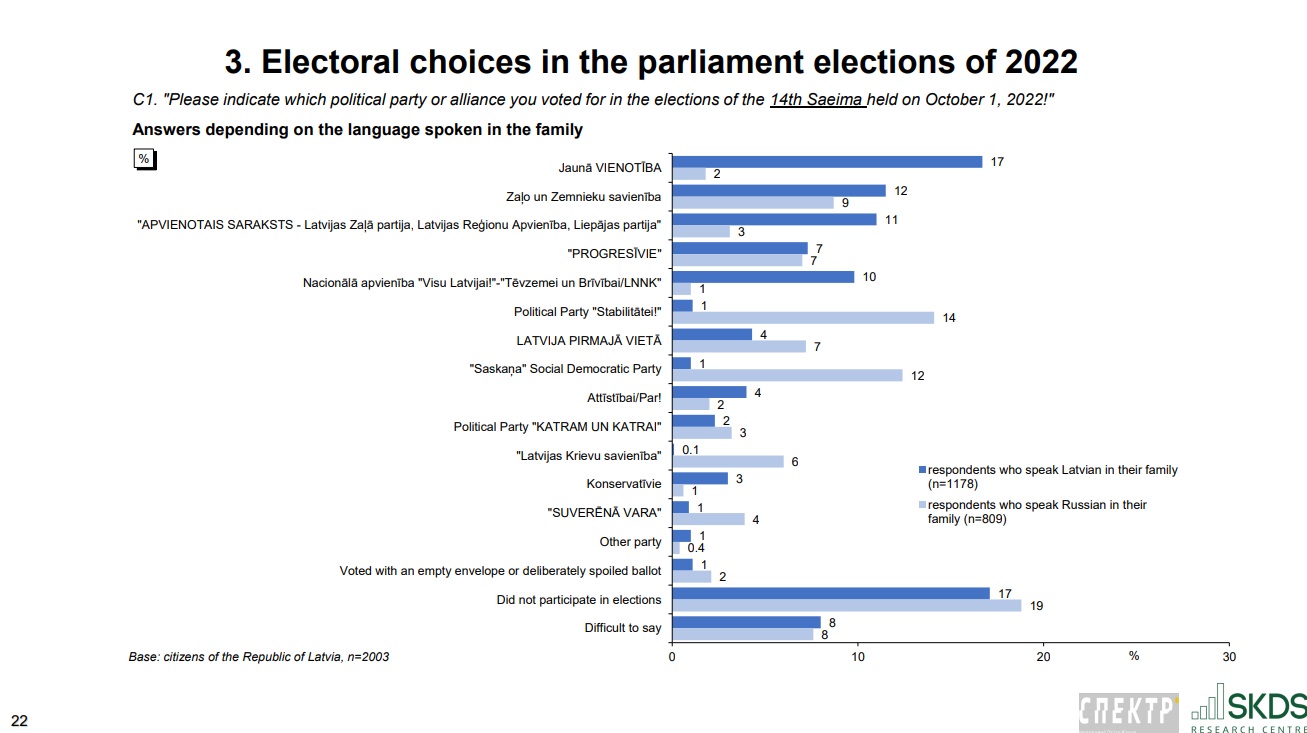

Like in other countries, in Latvia, «risk-takers» are more likely to support new parties that have just appeared on the political scene. Risk-averse people tend to vote for traditional parties. This trend is most noticeable in two aspects. First, the Russian-speaking «risk takers» of the new, openly populist «Stability!» party, Alexey Roslikov is favored significantly more often (25 percent) than the general public (six percent) and significantly more than the other «Russian» groups (17 percent risk-averse, 13 percent «other»). Among Latvians, three per cent voted for Roslikov, according to the survey. Secondly, the highest support for the National Union is among Latvians avoiding risks — 15 percent against nine percent in both other groups. It should be added that risk-averse Latvians were the least supportive of the other political long-term leader — «New Unity»: 10 percent versus 17 and 18 percent among risk-averse and «others» respectively. They, on the other hand, most often declared that they did not take part in the elections — 25 percent versus 20 percent and 16 percent.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

- Evaluating Latvia’s participation in various organizations, 77% of risk takers positively assessed Latvia’s membership in the EU and 72% of Latvia’s membership in NATO. Among risk avoiders 78% were favorably disposed toward Latvia’s membership in the EU and 65% of Latvia’s membership in NATO. It should be noted that when assessing Latvia’s participation in these organisations, risk avoiders were slightly more often than other groups «completely satisfied» with Latvia’s participation in these organizations.

- When analyzing the relationship between electoral choice and attitude toward risk, it can be concluded that risk takers are slightly more likely than respondents in general to choose parties elected to Saeima for the first time (e.g., Stabilitātei, Progresīvie, Latvija pirmajā vietā). Risk avoiders, however, prefer NA slightly more often than average. It should be mentioned that risk avoiders were slightly more likely than risk takers to indicate that they voted for Jaunā Vienotība, NA, Saskaņa and Latvijas Krievu savienība. It is interesting to note that Russian speaking risk takers were significantly more likely than other groups to prefer the Stabilitātei, party, while Russian speaking risk avoiders preferred Saskaņa and Latvijas Krievu savienība.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

Risk tolerance does not affect attitudes towards Putin

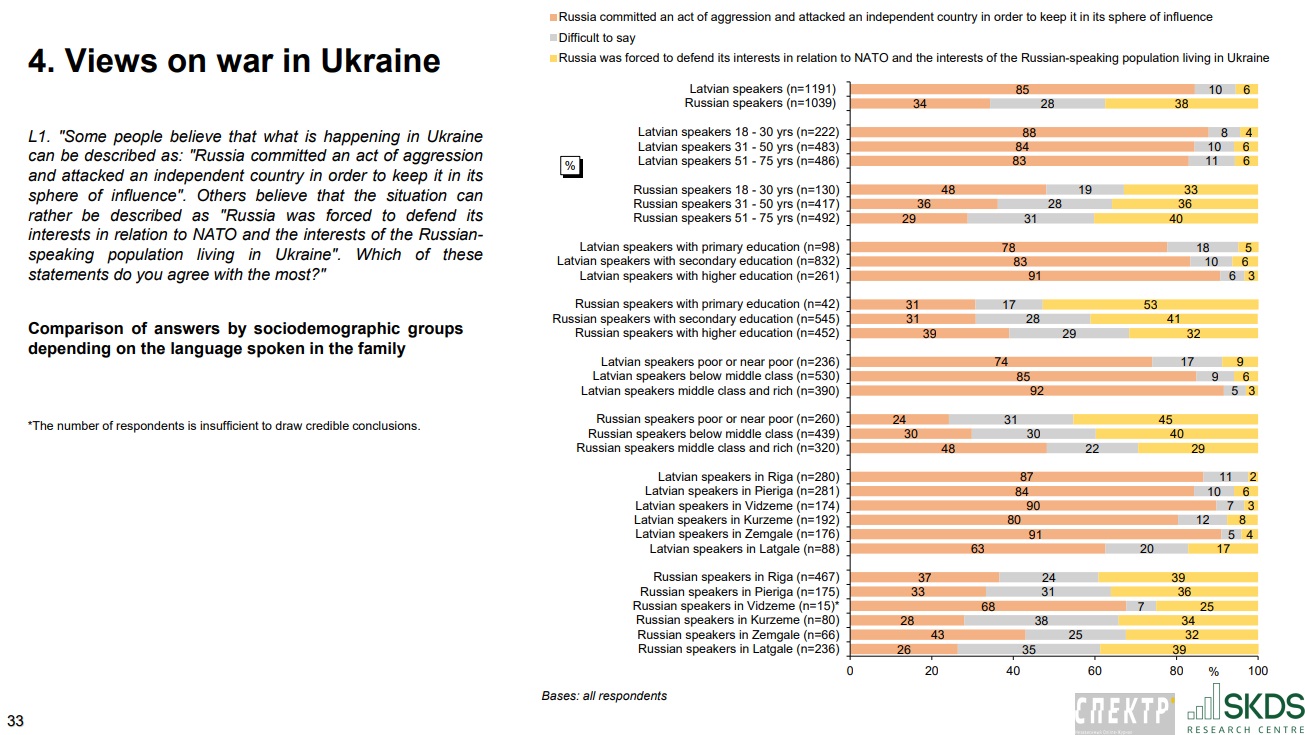

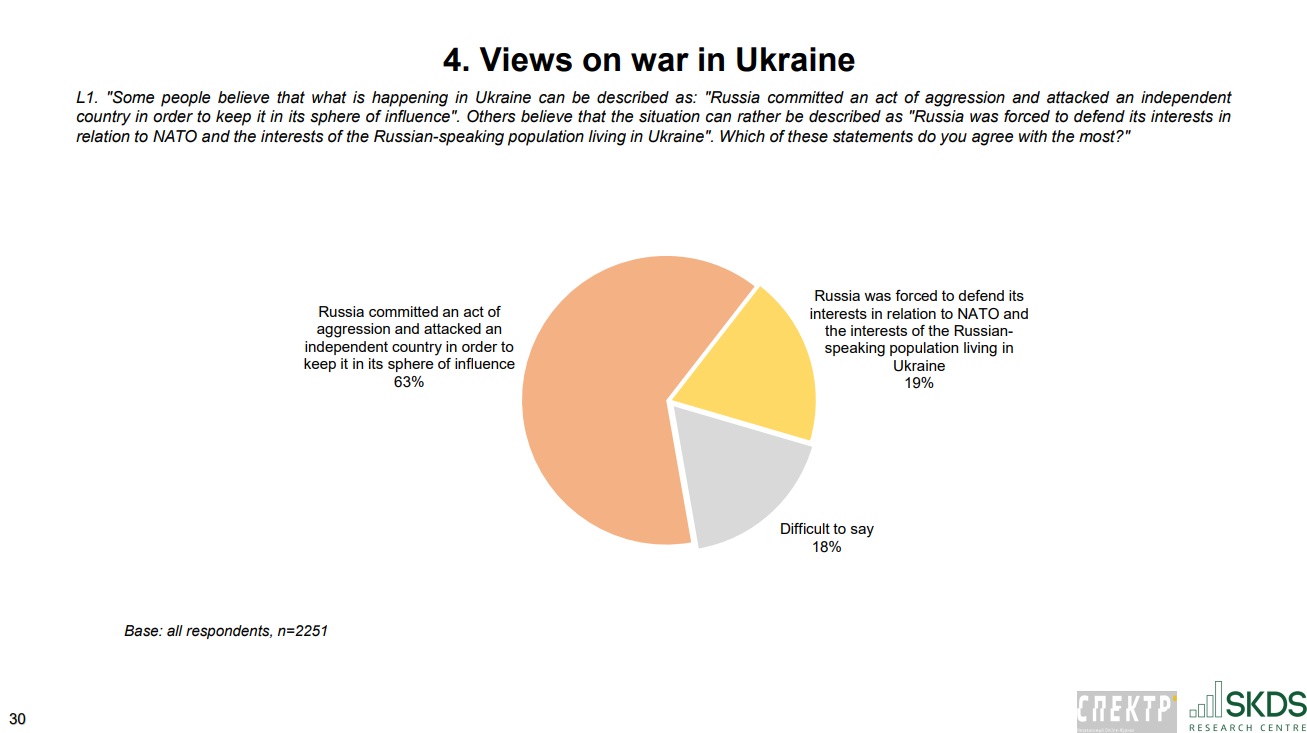

According to Procevska, the risk tolerance factor does not predictably affect the attitude towards Putin and the conflict in Ukraine. The native language of the respondents is most important. «We had several questions,» the researcher explains. «Firstly, we asked how people agree with certain narratives. Did Russia commit an act of aggression, or did it protect its legitimate interests in Ukraine?» 85 percent of Latvians and 34 percent of Russian speakers opted in aggression. Supporters of the version of protection of interests among Latvians are six percent, among Russian speakers — 38 percent.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

«But here it must be borne in mind that 28 percent of Russian speakers evaded answering this question,» Procevska emphasises. «It can be assumed that they did not want to demonstrate socially disapproved views. These are, most likely, the sort of people for whom «everything is not so clear.» As before, the attitude of the Russian-speaking part of society to the war is unknown to us. However, even among Latvians, 10 percent refused to answer. It’s a lot. We don’t know how they separate. Here it is even more likely that they considered their possible answer unacceptable and concealed it. Some people really don’t have an opinion, but there are usually three to five percent of them in any survey.»

In addition to language, age clearly affects the distribution of answers. In the group of 18−30 years old, there are 74 percent of people who designate this event as aggression, while among those over 50 years old — 58 percent.

The answers also correlate with the income of the respondents. The poor are less likely than others to speak out in favour of an act of aggression (50 percent), the middle class and above — in 74 percent of cases. «Perhaps people with low incomes perceive this narrative as the official position of the state and therefore, in principle, are against it,» the researcher suggests. «If among the poor Latvians 74% speak about the act of aggression, among the wealthy it is already 92% of them. Among the Russian speakers, there is also such a «ladder»: the poor recognise the act of aggression in 24 percent of cases, the wealthy — in 48 percent».

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

«The anti-elitist potential of our society is high,» Procevska says. «People’s views are quite dependent on where they are in the socio-economic hierarchy. And this is another reason to fight poverty. Probably, the «fifth column» is formed not where we usually look for it and becomes it for other reasons: not because they are Russians, but because they are poor. These people simply do not feel a fundamental relationship with the state, because they do not see support from it.»

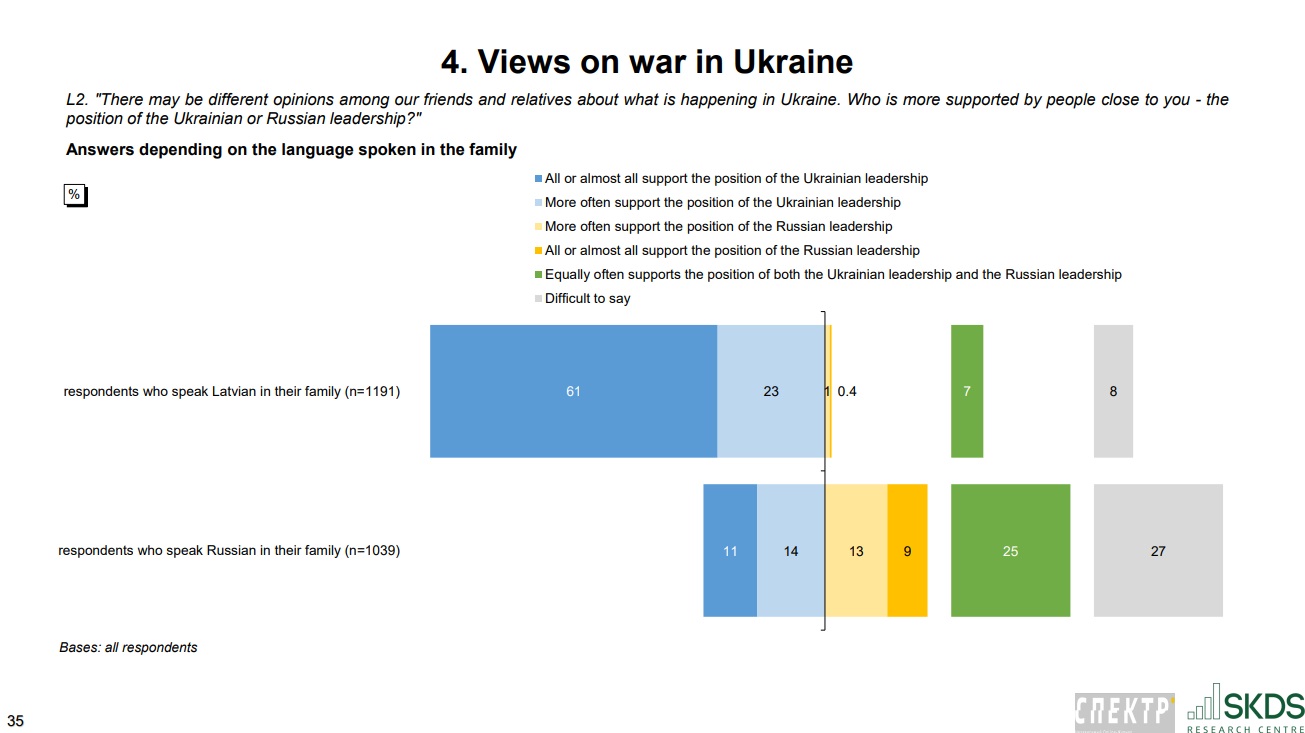

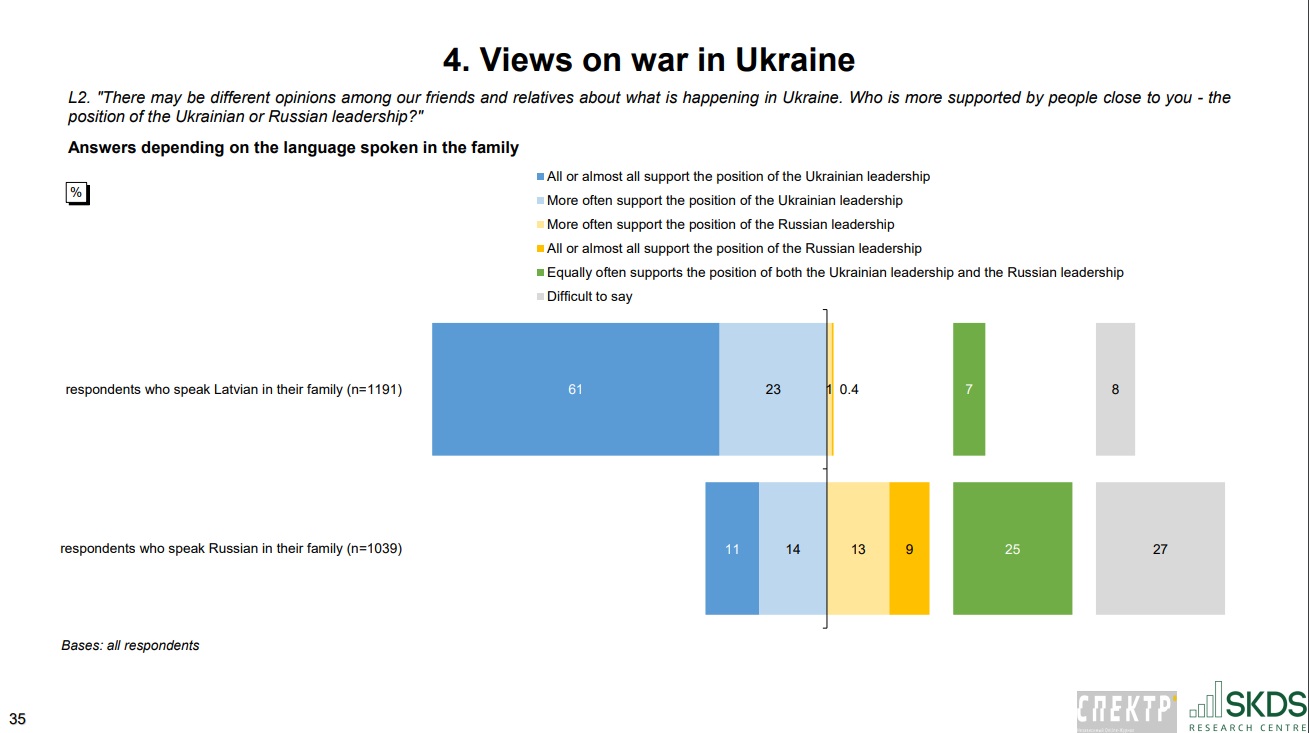

The second question, which concerned Ukraine, sounded like this: «Whom do your relatives and friends support?» Here, for simplicity, the researchers used the phrase «Ukrainian authorities» and «Russian authorities». 40 percent of respondents generally answered that everyone in their environment supports Ukraine. Another 19 percent that Ukraine is supported by the majority in their circle. That is, in general, 59 percent of respondents live in pro-Ukrainian information «bubbles». All or almost all people around support the Russian authorities in only four percent of the respondents and another six percent «support Russia more». That is, only 10 percent are living in pro-Russian «bubbles».

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

Another 15 percent of survey participants have the same number of friends and relatives who support both sides. «Among the Russian speakers, there are 25 percent of them, I wonder how these circles of communication develop,» Olga Procevska wonders. Another 27 percent refused to answer. Thus, Russian speakers are divided into several blocks of the same size and, apparently, they can maintain relations in their circle, regardless of their views. This is uncharacteristic of Latvians, who are more united: 84 percent of respondents have an inner circle who rather or fully support the Ukrainian authorities. «We know from other studies that Latvians, in principle, communicate more with other Latvians, while Russian speakers, as a minority, simply have to communicate more often in mixed communities,» the researcher comments on this result.

There is also a correlation in terms of income. The wealthier the respondents, the more people in their circle who support only Ukraine. Are the poor taking the side of the Russian authorities? No, the greatest correlation with the level of wealth is manifested in the «hard to say» group. Among the poor, 24% of respondents avoid answering, among the wealthy — 10%. «In general, in all these «war-related» questions we see a large group of people avoiding answering, and it is precisely this group that contains the most interesting results,» Olga Procevska emphasises. «When compared by regions, the most evaders are in Latgale — 28 percent, with an average of 16 percent».

It can be assumed, the researcher argues, that these are people who do not want to express their views because of their public unacceptability: «Literally poor Russian-speaking Latgalians sit and conceal their opinion on sensitive issues, though vote for Roslikov. They express their protest not by expressing in the questionnaire an opinion that runs counter to the mainstream. They will keep it to themselves. That’s what makes elections great, that a person enters a booth and makes a choice, being alone with himself.

- According to the survey data, risk takers assessing the events in Ukraine were more likely to say that «Russia committed an act of aggression and attacked an independent state to keep it within its sphere of influence» (66%, 62% in the risk avoiders group) and less likely (19%) to say that «Russia was forced to defend its interests against NATO and the interests of the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine» (21% in the risk avoiders group).

- According to the survey, 63% of risk takers said that their friends and relatives were more supportive of the Ukrainian leadership’s position (compared to 58% of risk avoiders). The fact that friends and relatives are more supportive of the Russian leadership was equally often reported by both risk takers and risk avoiders.

Russian-speaking fathers and their children

We asked several experts in the survey field to comment on the results of the research.

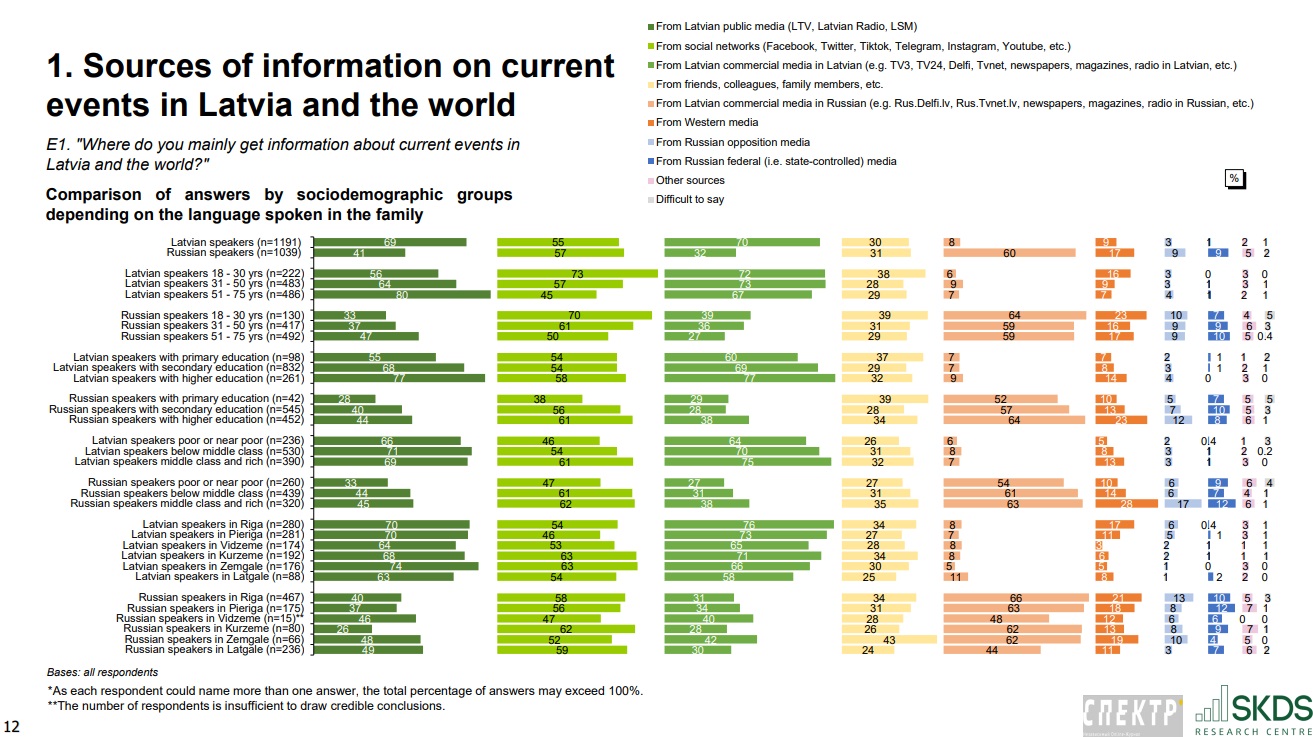

Juris Rozenvalds, Leading Researcher at the Institute of Social and Political Studies of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Latvia, noted a positive trend: the number of those who are positive about Latvia’s accession to NATO is gradually, but quite clearly, increasing. «Until now, it was believed that a significant part of the Russian-speaking population is under the influence of Russian media, but this trend suggests otherwise,» the political scientist says.

Rosenvalds also noted that the younger generation, unlike the older ones, does not have much confidence in the Russian-language public media (33 percent). «It’s good that they still focus on Latvian commercial media in Russian (64 percent), and not on Russian ones (seven percent),» the political scientist says. «It’s difficult to say what is the cause and what is the effect. Perhaps, they feel that the public media are linked to the state, which they don’t trust very much. Or, on the contrary, does the state itself reduce trust in them, in fact, keeping these media outlets on a «starvation diet» and at the same time wagging a finger at journalists, as if saying «look for another place of work, everything should be in Latvian?»

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

Mārtiņš Kaprāns, Researcher of the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the University of Latvia, expert of the Centre for European Policy Analysis, also drew attention to the fact that 60 percent of Latvian Russian-speakers get information about what is happening in Latvia and the world from the Latvian Russian-language commercial media. «The state media policy over the past few months has been aimed at increasing the consumption of content in Latvian and from Latvian media among Russian speakers,» the expert says. «And the survey data shows that this is to a large extent wishful thinking. A naive, populist, but unattainable strategy. I don’t see why on earth this majority would suddenly stop receiving information in Russian.»

On the other hand, he says, the survey data, combined with previously published studies, show that there is a large and stable audience (40−45 percent) among Latvian Russian-speakers, who can be called bilingual in nature. These respondents admit that they receive information in two languages, not only in Russian, but also in Latvian or, perhaps, in English. And, of course, the bilingual model is more represented among younger audiences.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

Iveta Kažoka, Director of the Latvian research centre Providus, once again, according to her, was convinced that the Latvian Russian-speakers are not a homogeneous mass. «For example, it is interesting that young people who speak Russian and those with high incomes are significantly more positive towards NATO than older generations and people with low incomes,» she says. «Also, in the context of the war, it is these groups that take a clearer pro-Ukrainian rather than a pro-Russian stance.»

Mārtiņš Kaprans noted that despite the obvious Euro-optimism of both communities towards NATO, the audience is splitting. While the attitude is distinctly positive in Latvians, it is generally negative in Russian speakers. Moreover, within the Russian-speaking community, polarisation on this issue is also obvious. Almost half of young people aged 18 to 30 are positive about NATO, while the rest, especially older people, are much more negative about its role. The poor are more negative than the wealthy. «The factors influencing the split of the Russian-speaking community are age and financial situation,» the researcher sums up. «Plus, the citizenship factor is not highlighted here, but I’m sure we would see an even greater difference between citizens and non-citizens.»

In answers to the questions about Ukraine, one can also observe this fragmented public opinion among Russian speakers in contrast to the Latvians with their clear consensus. Among Russian speakers, only a third agreed with the statement that in Ukraine we are dealing with Russian aggression, Mārtiņš Kaprans outlines. And more than a third, 38 percent of respondents, legitimise the invasion.

«And, besides, there is already famous, huge, in fact, part or 28 percent, of people who refused to answer, or who «difficult to say,» the expert at the Centre for European Policy Analysis says. «Their number remains approximately the same during the year [of the war]. Why? It can be assumed that some still do not understand what happened. Others may not want to take a clear position, because it will force them to take some kind of symbolic responsibility towards other Russian speakers.»

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

Thus, in Latvia, Mārtiņš Kaprāns concludes, a contradictory situation persists. In general, one opinion is maintained in society — about Russian aggression. However, among Russian speakers, especially if you live in such pronounced Russophonic places as Riga or Latgale, it can dominate, on the contrary, the notion that Russia was «forced» to attack: «There are two different competing and at different levels meaningful views. Therefore, a person prefers not to take a position. It is important to understand that this fragmentation in relation to Ukraine persists throughout the year. We can cut the Russian-speaking community into three parts. And here, too, we see a generational split. Probably, this phenomenon, which you may have seen in Vladislav Tokalov’s film «Everything will be fine», was clearly manifested in these data.»

Fragmentation of Russian speakers is also noticeable in answers to the question of support for the authorities of one or another side of the conflict: 25 percent support the Ukrainian authorities, 22 percent support the Russian authorities, and 27 percent (this is the largest part) find it difficult to say anything definite. «But the most interesting group is the fourth one,» the researcher says. «A quarter of the respondents, who cause bewilderment, at least among Latvians, because they agree with both sides. This is contrary to the laws of formal logic. I think this is their actual position: they are ready to understand both Zelensky and Putin at the same time.»

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

What does this mean in their daily behaviour and practice, Mārtiņš Kaprāns wonders. «At the same time, do people feel sorry for the Russian aggressors who are dying in Ukraine and the Ukrainian victims whom these Russians are killing? We are talking, of course, about situational attitude and identification. Who are these people? This is not characteristic of predominantly Latgalians or predominantly poor Russian speakers. Slightly more often than average, this indefinite position is characteristic of the older generation. But in general, this group does not have any socio-demographic markers.»

Juris Rozenvalds, on the contrary, notes that the number of respondents who choose the answer «I don’t know» has decreased since the last known surveys, while the number of those who made up their mind has increased, and, unfortunately, on both sides.

Political preferences of Russian speakers

Martins Kaprāns notes that 35 of Russian speakers support moderate political powers, including not only so called «Russian parties», but also the Union of Greens and Farmers, Progressives, Latvia First and Harmony. According to him, For Stability! and Latvian Russian Union that gained 20 percent support in aggregate represent the radical wing.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

The Union of Greens and Farmers, Progressives and Latvia First! that have always been considered as non-Russian parties gained 23 percent of Russian speakers’ votes in aggregate. It is an impressive result given that the Latvian Russian Union got only six percent. «This is the first statistically grounded confirmation of the fact that the choice of former supporters of the Harmony was affected by the party’s insufficiently clear position with regard to both Russian schools and the monument,» Kaprāns notes. «However, it is also interesting the stance regarding the schools and monument was merely neglected by young respondents. And it is one more evidence of a generation gap.»

In this regard, Rozenvalds disagrees with Kaprāns and notes that despite the popularity of the Progressives and Union of Greens and Farmers (UGF) with Russian speakers, the system of parties based on ethnicity persists. Rozenvalds was surprised that approx. 30 percent of Russian-speaking voters argued that they had never voted for the Harmony. «This has nothing to do with the past situation, in which the Harmony was a sort of an umbrella for a Russian-speaking voter,» he remarks. «On the other hand, the fact that many Russian-speaking voters did not vote for the Harmony as they «regarded the party as boring» came as no surprise.»

Game changers without university diplomas

Martins Kaprāns thanked the authors for the data on respondents’ income. «We usually neglect this matter as unimportant: to which extent specifically ethnic inequality is noticeable in Latvia,» he says. «Obviously, we are talking about subjective perception of financial prosperity rather than objective data. According to the results of the survey, there are hardly any grounds for ethnolinguistic social economic segregation in Latvia.»

The sociologist notes that in the segment of economically disadvantaged (these are two first levels) Russians prevail over Latvians by 6 percent, nevertheless, he believes that this parameter is close to a statistical spread. One quarter of Russian-speaking respondents believe that they are poor, however, much more in fact, three thirds referred themselves to the middle or wealthy class. Therefore, Kaprāns concludes that it seems that the narrative arguing that Latvia has failed as a state disseminated from Russia and aimed at Russian speakers does not work.

Although, he noted a less positive trend: it seems that young Latvians feel more successful than their parents as they refer themselves to disadvantaged groups much less frequently than older people. In the Russian environment that situation is more even.

Representatives of both communities respond to the question about their material status in their childhood similarly. In two lower groups, position of 10 percent of Latvians given their answers has improved over the years, i.e. when they were children they were less wealthy than now. While Martins Kaprāns does not note such a positive dynamics among Russians. He reminded that we are talking about a subjective evaluation: «Latvians believe that economic status of the country has improved since they were children, while Russians do not share this opinion. Russian speakers at the age of 55+ are the least supportive of this point of view. I do not think that we are talking about objective wealthiness. It is hard to imagine that people were richer than now during the years of decline of the USSR. Perhaps, it deals more with the social status that they might feel they lost.

Source: «Research report: risk tolerance of Latvian residents and their attitude towards current events"/ Spektr. Press / SKDS

Philosopher, publicist, docent and leading researcher of the University of Latvia, editor of the online magazine Satori Igor Gubenko is the only commentor who evaluated the results of the research in risk tolerance among inhabitants of Latvia. «The social and demographic landscape itself is interesting,» he says. «We do not see any considerable difference between Russian-speaking respondents and Latvians, except for Vidzeme, where 34 percent of Russian-speaking respondents are referred to the group that avoids risks.»

In no other geographic region there is more average weighted risk-averse respondents among Russian speakers. Igor Gubenko asks himself what the reason can be: «Vidzeme is a region, in which Russian-speakers are present as minority. It is the most Latvian region of the country in terms of language. Perhaps, the result shows conformism resulting in lack of initiative, readiness to radical changes. This quality contributes to the overall conservative approach to choices in life.»

Gubenko admits that he was confused by the first part of the research devoted to the evaluation of current events. «Those show that higher education is the most important factor for critical thinking, media literacy among respondents,» the expert notes. «The share of those who finished only secondary school is the largest in all three groups that mark attitude towards risk and it represents actual ratio among the population. However, the Russian-speaking segment illustrates that there are 72 percent of risk-takers who completed secondary education, considerably more than in two other groups of attitude towards risk (62 percent among risk-averse respondents and 49 among «other»).»

Igor Gubenko considers that aspect from the point of view of the electoral choice. In general, the population of Latvia shows low risk appetite, in this light, it is interesting to consider the fact that the same political power being in the centre of the coalition has maintained leadership for more than 10 years. The predominance of «risky» secondary-school-educated Russians results in popularity of parties whose sentiment could be described as «Away with elites!», Igor Gubenko continues. Indeed, we see that new populist political powers appear in the parliament, he notes. Russian speakers vote for the Stability! not because the Harmony has quit the scene and there is nobody else to vote for, but rather because this very party reflects their hopes, the editor of the online magazine Satori argues. 25 percent of risk-taking Russian — the greatest share — voted for the Stability!.»